Gratitude

At this time in our secular year, we are supposed to be thankful. Of course, we should be thankful all year round. Our Jewish tradition has almost endless ways to say thank you.

The book that I’d like to bring to your attention is not a specifically Jewish book, but its premise of thankfulness is very Jewish.

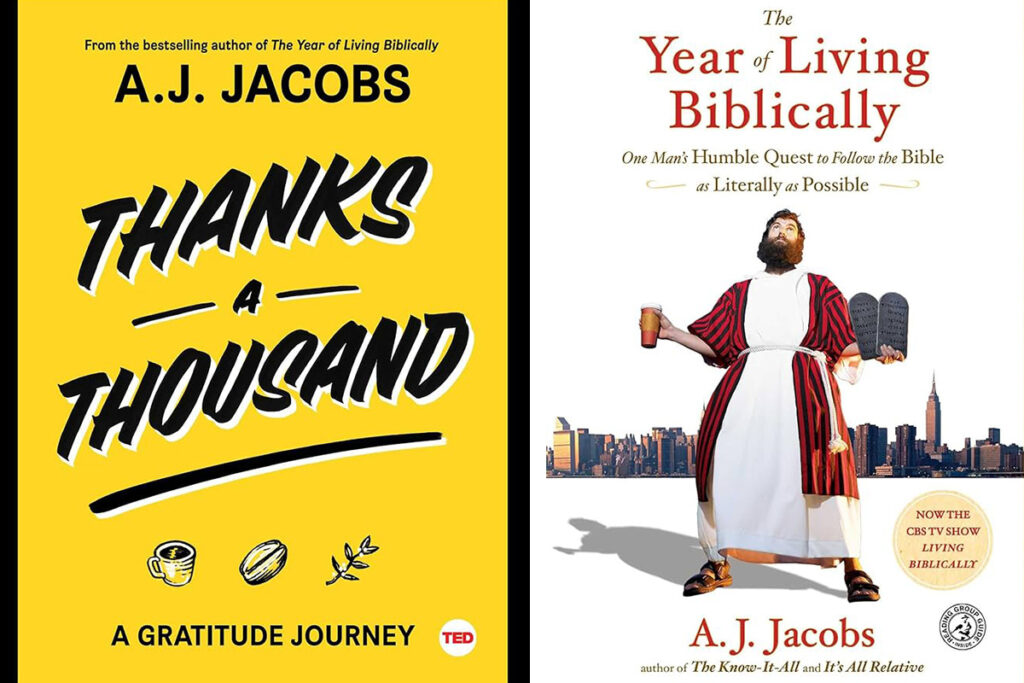

A.J. Jacobs has made a literary career of immersing himself in a topic: he’s spent a year living Biblically, which he describes in The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible. He has attempted to live as the Founding Fathers did, which he writes about in The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution’s Original Meaning. He’s tried to become a know-it-all by reading his way through an entire encyclopedia in The Know-It-All: One Man’s Humble Quest to Become the Smartest Person in the World.

In 2018, inspired by a conversation with his then 10-year-old son, he decided to be thankful, and in Thanks a Thousand: A Gratitude Journey sets out to thank everyone associated with the cup of coffee purchased at Joe Coffee, his local coffee shop.

From the owner of the shop to the manufacturer of the cup to the farmers and distributors, Jacobs discovers how intricate the world of the simplest thing is. It is almost overwhelming but also illuminating as the reader realizes how interconnected our world and its bounty are. Jacobs says,” If we connected the world with threads signifying gratitude, the result would be as thick as a blanket.”

How grateful people are to be noticed and thanked.

You may not want to rush to the nearest coffee bar to say thank you, but as we approach Thanksgiving, you might be inspired to be more appreciative of whoever puts food on the table in your home.

As Rabbi Nachman of Breslov taught, giving thanks for even the smallest thing is important. For him, gratitude was a path to joy and connection with God.

Mamdani, Mikie, and Making Minyan

Somewhere between Mamdani and Mikie, between the government shutdown and canceled flights, a week of normal life went by. I ate more than my share of leftover Halloween candy, got Eloise off to school, served my weekly stint on a grand jury, and called the tree guy about the storm-damaged oak in my backyard. God did not appear to me as in the Torah’s opening verse this week, when Abraham sat “in the heat of the day” outside his tent. But I talked to God a lot — not only because 5786 is about renewing my prayer life, but because there is a lot to discuss.

“Will you sweep away the righteous with the wicked?” Abraham asks. That’s our question, too, these days. Aren’t there so many good, righteous people worth caring for? Whether it’s immigration raids or SNAP benefits, we share with Abraham that yearning — that the existence of righteous people might itself be reason enough to save the place. Rabbi Avital Hochstein, drawing on Onkelos and Rashi, teaches “in light of the presence of the righteous, [there is by Abraham] a call for God to tolerate, to bear, to accept or even absorb evil — to refuse to let the wickedness of others dictate God’s response.”

In other words, Abraham asks that we be judged by the merit of those who choose good and justice, not condemned for the worst among us. That feels vital now, not because I fear God’s wrath but because I worry about ours.

None of us — not our leaders, not even our enemies — are wholly righteous or wholly wicked. The Mishna says our lives are a balance of both, and our task is to keep tipping the scales toward good. That’s teshuvah: trying again and again, convinced that inside each of us is a spark of light longing to shine. Rebbe Nachman of Breslov warned against despair; he taught that our sense of darkness only blocks the light from breaking through. We must find the light within ourselves — even one small point — and let that holy spark light up the world around us. And we must find the light in one another, too.

Neither Mamdani nor Trump is pure evil or pure good. Whether you voted Republican or Democrat — and I love that we are a congregation of both parties — whether you love everything or nothing about what the administration is doing, Abraham’s argument is not only with God, but with us. Generalizing based on despair and seeing only the worst of a society is not right. It is not good to dismiss people, cities, or entire nations out of outrage.

Abraham, God’s chosen one, negotiates. If ten righteous people can be found, don’t destroy the city. God agrees. That’s how we get 10 for a prayer quorum in Jewish life: if we have 10 willing to pray — to hope, have faith, see the good – it’s worth saving the city. And because people aren’t wholly good or wholly bad — if we can find even a tiny percent of goodness in everyone, including those who cause us despair, we emulate God. We tip the world toward justice through patience, compassion, and the courage to keep seeing light in dark and complicated places.

Maybe that’s the real work of this moment: to refuse despair. To speak with God not only when we see angels at the tent door, but when the oak is split, the flights are canceled, outrage runs high, and mercy feels impossible. To keep looking for that tenth — in others, in ourselves — and believe we still have the power to save the world.

The Golden Pages Book Club

Hello, Readers!

I am looking forward to the first Golden Pages Book Club on Thursday, November 6. There is one copy of Threadbare left in the library. The other two books in the “Gilded City” series are also available. All the books have recurring characters.

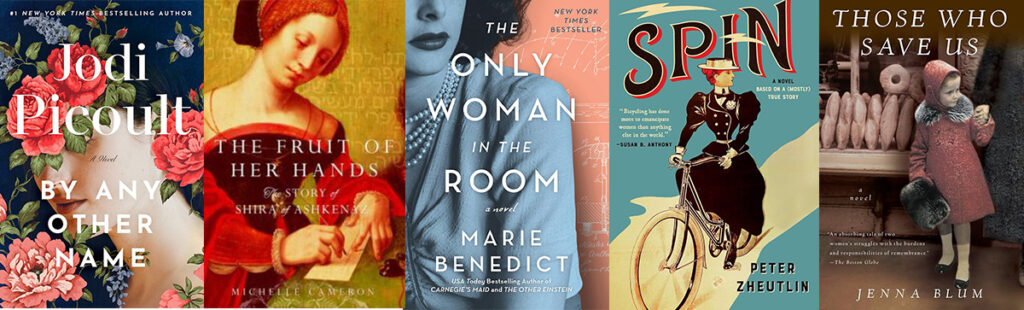

The following list is a group of books that you may enjoy if you like historical fiction, the same genre as Threadbare. Keep in mind that all these books are based on at least a kernel of history, and many are much closer to historical reality than we might believe.

This list only scratches the surface of historical fiction in the adult section of the library. In addition, there are crossover books in both the Young Adult and Juvenile sections.

Benedict, Marie. The Only Woman in the Room. Did you know that Hedy Lamarr was not only a beautiful movie star but also a scientist? This is her story filtered through the genre of historical fiction.

Blum, Jenna. Those Who Save Us. Set after World War II, this novel focuses on the main character’s inherited shame and guilt over her German heritage.

Cameron, Michelle. The Fruit of Her Hands. The story of Shira of Ashkenaz, the wife of famed Rabbi Mair of Rothenberg, is based on mere snippets of history, as are the lives of most medieval women. However, Jewish history comes alive as experienced by this extraordinary 13th-century woman.

Carner, Talia. The Third Daughter. Fourteen-year-old Batya and her family escape Russia’s pogroms, but instead of finding freedom in the United States, she is tricked into the promise of marriage and ends up being sold as a prostitute in Buenos Aires. Unfortunately, this sex trafficking really happened.

Edwards, Shaunna. The Thread Collectors. Talented Black seamstress Stella and New York Jewess Lily find themselves drawn together by the fates of their husbands, soldiers in the Civil War, and their stitchery. There is, indeed, power in women’s work.

Hertmans, Stefan. The Convert. In 11th-century France, Christian Vigdis Adelais, daughter of a celebrated knight, falls in love with David Todros, a yeshiva scholar. Can anything good come from this romance? Great local color as the characters travel through Europe seeking a safe haven.

Kadish, Rachael. The Weight of Ink. This is a novel of history, women, and Jewish identity. Using a split-screen format, the author tells the story of London Jewish life in the 1660s and scholarship in the early 21st century. The story unites two remarkable women through some rediscovered 17th-century documents.

Picoult, Jodi. By Any Other Name. This is another split-screen plot, taking place in Shakespeare’s time and contemporary New York. Under consideration is who really wrote Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets, as well as the value of women’s creative work. The title tells it all.

Zheutlin, Peter. Spin: a novel based on a mostly true story. In 1895, Bostonian (but Jewish immigrant) Annie Londonderry began an around-the-world bicycle trip. This jaunt was declared “ the most extraordinary journey ever undertaken by a woman.” Whoever dreamed that Annie Cohen Kapchovsky could and would do such a thing? Zheutlin is a descendant of Annie.

Kol Nidre Address (Oct 1, 2025)

Opening

This morning, the first thing I did was grab my phone and scroll – and unfortunately, it was a doom scroll, not a hope scroll as Rabbi suggested on Rosh Hashanah that we should all aspire to. I was bombarded with news about Israel’s war, antisemitism raging around the world, and the seemingly endless cycle of political division and discord. It came to me through social media, news alerts, and WhatsApp messages. I started my morning with a pit in my stomach, a heaviness hard to describe in words, and thus all the more isolating. Sadly, this feeling was not a new one. For the past two years, it has become my normal.

We all have different strategies to cope. We walk, meditate, bike, practice yoga. I love pilates and crossword puzzles. We pray — sometimes in the sanctuary or chapel, oftentimes quietly in our hearts as we go about our day. We do these things, and they help. But if we’re truly honest with ourselves, they don’t make the pit go away.

So what does? As the late relationship expert Dr. Sue Johnson often reminded us, humans are social mammals. Study after study confirms what our hearts already know… we are wired for connection. Connection to our spouses, family, and friends, to our community. Connection is the essential antidote to that pit.

A year ago, I stood here and told you that living a Jewish life was an important act of resistance to insidious antisemitism. That remains true, perhaps more than ever. But today, a year later, I want to focus on something equally powerful that living a Jewish life can provide: joy. The joy that flows from connection. The joy that comes from being part of a Jewish community — from our oneness as a people.

I often see this joy in the lives of my cousins in Israel. I chat with them and follow their lives on social media – at least the fun parts — my cousin Lihi’s wedding at the dairy moshav of her husband Shlomi’s family, vacations, trips with their kids to the beach, fancy cocktails with friends, leisurely time with family.

What I see is that Israelis are living their lives, in the midst of a war, finding joy where and when they can, with their extended community — living their lives as Jews who refuse to succumb to those who seek to destroy them. And I want that for all of us.

Judaism had figured out the importance of connection long before Dr. Sue Johnson’s research. It is a communal religion by design. We mourn together, we celebrate together, and even our prayers reflect this concept.

Vidui and Unity

Take the Vidui as an example. It is the confessional prayer we recite on these holy days, and it has us speak in the plural. It does not say I have sinned — it has us say ashamnu, bagadnu, gazalnu — we have sinned, we have betrayed, we have stolen. Our tradition teaches that we are all responsible for one another, that the failings of one touch us all.

We are not alone. And that is where the deepest joy of Jewish life comes from — knowing we are not alone, but bound together, finding strength and resilience in one another.

Differences Not Divisiveness

Yet, experiencing that joy — that beautiful sense of being bound together — isn’t always easy in practice. Despite our oneness as a people, the simple fact is that we don’t all think alike. You know the saying: put 100 Jews in a room, and you’ll get 100 opinions…and that often feels like an understatement! And sometimes — let’s be honest — our differences lead to conflict. We disagree over Israel, over politics, over how to practice our Judaism. We debate and argue, and that’s actually very Jewish of us. But we cannot let disagreement devolve into divisiveness.

We need perspective.

Over the past year, I read many statements from released hostages and hostage family members. Each and every one called for unity. I was particularly moved by the words of Eli Sharabi, shortly after being freed from Gaza — a shadow of his former self, yet still strong enough to say this:

“Sometimes, within the noise, in the division, in the shouting, we are forgetting the most basic thing: We are in this together. One blood. One heart. One. And when our enemy sees us as one, maybe it is time for us to see the same thing in ourselves. Because only together will we win. Straight up.”

If he could see this with such clarity in his darkest hour, surely we, in our freedom, can embrace it too.

Rabbi Treu often speaks of her desire for a “big tent” — a place where each person can bring their whole self, knowing there is space for individuality, while also acknowledging our deep connection to one another. We cannot let our differences get in the way of that joyful connection. Because without it, without each other, we lose the antidote to that isolating heaviness that I spoke of earlier.

My sincerest hope is that in this New Year, we will chart our path toward unity — not by thinking alike, but by listening deeply, and by remembering that we are, fundamentally, one people. Because it is only in that unity, in that connection, that we can truly access the joy of Jewish living.

Celebrating Judaism, L’dor V’dor

Together, we must celebrate our Judaism. We must cherish it. Teach your children, your grandchildren, your non-Jewish friends, what it means to be and to live as Jews.

I saw the power of this, in the pure voice of my 3-year old grandson Cooper. He attends preschool at Park Avenue Synagogue in New York. Last summer, in a beach house rental, I brought along a ziplock bag containing candlesticks, kippot, and a tie-dyed challah cover my daughter Nicole made when she was in preschool – I’m sure some of you have the same one at home. The bag sat on the kitchen table. Cooper pointed and said, “LoLo (that’s what he calls me), there’s Shabbat in there.”

And from the wonder in his voice, I knew that Gary and I might have done something right… that the cycle continues. But it only continues if we keep living it, teaching it, and celebrating it together.

How to Use Oheb

So my friends, that is why Oheb Shalom matters. This synagogue isn’t just a place to attend once or twice a year out of a feeling of obligation. It is a place to root your children and grandchildren in Jewish joy. To learn and grow as adults through study and discussion. To celebrate, to mourn, to mark joyous milestones with your Jewish community. To belong and feel connected as one Jewish people.

And it is because Oheb Shalom does matter, that it is essential we prioritize it, and that we support it. This year, instead of a Free Will Address on Rosh Hashanah, we shared an FAQ about synagogue finances. It dawned on us that many people don’t understand how the finances of Oheb work. I hope you saw it in your prayer book on Rosh Hashanah and in our newly printed Directory, and I hope you read it. It explains why our Annual Funding Appeal — a new name for our former Free Will Campaign — is critical to sustaining our sacred home.

We need your time, and your financial support, to ensure that Oheb Shalom continues to thrive for us and for generations to come.

Closing

So yes — it is difficult to be a Jew today. But it is also a blessing. Because when we carry one another through the heaviness, when we choose joy in Jewish living, we all come out stronger. My grandson Cooper saw the joy of celebrating Judaism in a ziplock bag; where do you see it?

My blessing for us this year is that you see it here at Oheb Shalom, so that we can pass this beautiful community from one generation to the next.

G’mar chatima tovah. May we all be inscribed in the book of life, and may it be a good and sweet and healthy year, for us, our families and our people all around the world.

Genesis

Some first families live in white houses. Others live in palaces. Our Jewish first family lived in

Paradise, in the Garden of Eden.

Of course, the first family was unable to follow the rules and got itself evicted from Paradise.

That event also — in simplistic terms — defines one of the main differences between Judaism and

Christianity. The Fall, as it’s called in Christianity, is the reason for humanity’s suffering.

In Judaism, again in simplistic terms, the lack of discipline on Eve’s part allowed humans to

grow and use the gifts that God gave them.

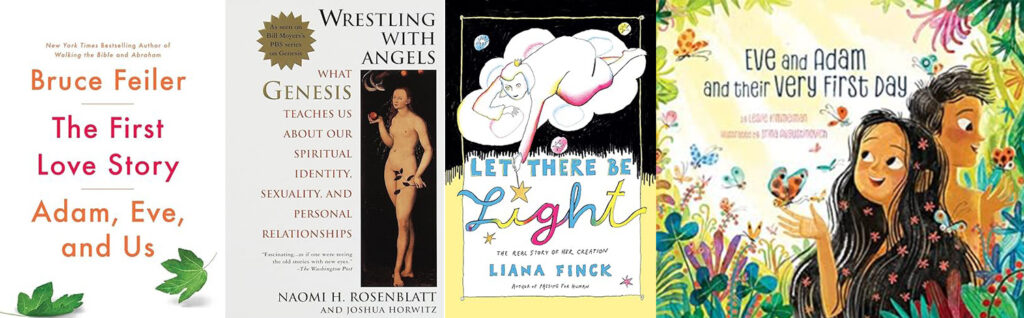

As we begin to read our Jewish story again, readers might be interested in investigating how

thinkers interpret the stories in Genesis for both child and adult readers.

The following are some of the books on Genesis in our library:

Reading Genesis. A collection of essays by experts in fields such as psychology, literature,

and law sheds new light on the text of Genesis.

Feiler, Bruce. The First Love Story: Adam, Eve, and Us. The author explains how Adam and Eve

serve as models for relationships, family, and togetherness.

Finck, Liana. Let There be Light: the real story of her creation. This graphic novel version

reinvents the story of creation with God as a woman.

Kimmelman, Lesley. Eve and Adam and the Very First Day. (Juvenile)

Levine, Amy-Jill. The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians Read the Same

Stories Differently.

Moyers, Bill. Genesis. Explores the contemporary relevance of the stories in the Bible’s first

book.

Rosenblatt, Naomi. Wrestling with Angels: What the First Family of Genesis Teaches Us About

Our Spiritual Identity, Sexuality, and Personal Relationships.

Sasso, Sandy. Adam and Eve’s First Sunset. (Juvenile)

Zevit, Ziony. What Really Happened in the Garden of Eden. Drawing on a variety of academic

disciplines, the author discusses what the story of Adam and Eve probably meant to the ancient

Israelites.

As If: Choosing to Believe (Yom Kippur 5786)

To watch the sermon, click here.

When 20-year-old Agam Berger was released from captivity in January, she walked onto an Israeli military helicopter, and—like the other released hostages—was handed a small white board so she could write a message to the world. Cameras were waiting, her family was waiting, Israel was waiting. She could have written anything, or nothing at all. But her words reverberated around the Jewish world, as we watched with tears in our eyes.

In shaky handwriting, she wrote words of gratitude to Am Yisrael, the Jewish people, and the IDF heroes who had risked their lives to rescue her. But above that, her first words, she wrote, “I chose the path of faith, and in the path of faith I returned.”

Mind-blowing. She had been kidnapped, lived in terror, held underground for weeks, and subjected to things beyond imagination. What does it mean to choose faith, when there is every reason to despair? What does this mean for us, sitting here today on Yom Kippur?

Because I bet if I took a straw poll right now—of the many reasons why you are here today, faith would not even register in the top five.

******************************

“What are you writing your sermon about?” a friend asked me on the phone the other day. “Faith,” I told her. “Isn’t that for Christians?” she asked. I laughed and thought: Exactly.

My dear friend Rabbi Lori Koffman once told me about her very first days of chaplaincy training at a hospital in New York City. She was still a student then, still trying to figure out what it meant to be a rabbi, when she stepped into an elevator one afternoon and found herself standing with a woman she had never met.

The woman turned to her and asked, “Do you know where the chapel is?” Rabbi Koffman nodded, ready to point the way—but before she could answer, the woman continued: “My sister just gave birth, and the baby is struggling. I just need a place to pray.” Rabbi Koffman hesitated for a moment, then leaned into her new role and said, “If it would help, I’d be glad to come sit with you and your family.”

The woman’s face lit up: “That would be great.”

They got off the elevator together and entered the chapel, where the whole family had gathered. The woman announced to everyone: “You won’t believe what happened! I was on my way to pray, and the chaplain was right there in the elevator. God sent her to us—just when we needed her.”

Later, Rabbi Koffman reflected: I didn’t see it that way. To me, it felt like coincidence. But for her, it was God’s hand, clear as day. And that made her wonder: What if she was right? What if God was there, and I did not know it?

******************************

Or take my friend Jeff, an Episcopalian minister whose wife went in for routine surgery and never made it out. Who just married off a daughter who lost her mother only a few months before the wedding. Who went on vacation by himself because he’s widowed now and has no one to go with.

At the pool one day, he watched a woman helping an old man into the water. And in that moment, he felt—he knew—that God was there with him. That the simple act of kindness he was witnessing was a portal into God’s presence. Despite his grief and loneliness, he felt God was with him, poolside.

******************************

We have so many reasons not to believe. We’re smart, educated, skeptical. We pride ourselves on our intellect. We know science, physics, biology. Who needs God? It makes zero sense, and we went to college and university, and we’re not that dumb.

Also, we know Job’s ancient question: if there is a God, why do good people die young, why Holocaust, why war and tsunamis, catastrophes that insurance won’t cover because they are “acts of God”? I mean, who wants that God in their life? No, thank you.

Or, we look around and see religious zealotry, the ways religion gets twisted, Jewish or otherwise, into something harsh and fanatical.

But here’s the thing: all of our skepticism and shifting around in our seats, avoiding the topic, is the answer to the wrong question. I’m not here asking why do you believe or not believe. I’m asking: what would it do for us, for the world, if this Yom Kippur we chose to believe? Like Agam’s handheld sign – we might choose the path of faith.

After all, Judaism does not require belief as a membership card—so it is going to have to be a choice that we make. Yes, there are certain beliefs that disqualify—belief in more than one god, for example, or worshipping gods of another religion. But beyond that, there are so many choices, so many ways to choose faith.

Jewish faith is not about certainty. Faith is about possibility. It is about choosing to live as if.

And yet—we psych ourselves out of it.

I’ll tell you a story I love. Some Jewish friends ended up in conversation at some kind of function with a group of people who weren’t Jewish. These people were full of questions about Judaism, and so the Jews are explaining about peoplehood and history and community and holidays and food. Then came the question: “What about God?”

“Oh, we don’t believe in God,” they said. The people who weren’t Jewish looked puzzled. As they continued asking, the Jews found themselves explaining that Judaism is more than “just” a religion, it’s a culture, it’s a values system, etc, etc, and finally one of them said: “So wait, are you saying that in Judaism, God is a bonus?”

Yes. Exactly. I love that line! God is a bonus. You can be Jewish without faith. But why would you do it without the bonus? It costs you nothing and gains you so much! For me, God is the bonus that makes the whole thing stick together. I know that’s not true for everyone, though. The story is funny because we can feel the truth in it, how there are so many ways to be Jewish and live a rich Jewish life, and even come here on Yom Kippur that have nothing to do with God, but let me say, as your rabbi: we are also a faith. Why are we giving up on that? Why wouldn’t we give ourselves the bonus?

I laughed recently when I looked at the books on my night table. On one side: Super Attractor by Gabrielle Bernstein. On the other: Emunah v’Bitachon—Faith and Trust—by the Chazon Ish, Rabbi Avraham Karelitz z”l. One’s a bestselling self-help guru from Westchester who has her face on the cover; the other, an early 20th-century Orthodox rabbi from Belarus who made aliya in 1933, settled in Bnai Brak and became one of the leaders of the Haredi ultra-orthodox community who is known by the name of his series of writings on Jewish law, who also sold millions of books. They could not be more different.

And yet—they’re saying the same thing. Gabby (as she calls herself) invites millions of people to “trust the Universe.” – capital U on Universe. You can go on her website and join the 21-day Trust the Universe Challenge, or you can buy her journal, where you list what you want to manifest in your life. The Chazon Ish wants you to take on pray every day and adhere to Jewish rituals as a means of cultivating emunah (faith) and bitachon (trust). She has a 3-step process she calls Choose Again – where, get this, you first notice the negative thoughts patterns or feelings, then you forgive yourself for it, and then you choose to do it differently. I’m sorry, but isn’t that exactly what we are doing here? Isn’t that teshuvah? His recipe would be what Maimonides teaches: you do teshuva, but asking forgiveness for the thing you did, and then when you’re in the same situation next time you don’t do it. It’s the exact same thing. Both tell us that if we do these things, then we will achieve a sense of serenity and calm. She talks about manifesting abundance; he talks about seeing God’s goodness everywhere so you feel the abundance of God’s blessings. Different words, different audiences, but over and over again the same messages.

Here’s the question: why can we stomach “trust the Universe” when it’s in English, but psych ourselves out of it when it’s in Hebrew? (And it’s not just that Hebrew is hard for us, I don’t buy that it’s just a linguistics issue.) Why do we embrace a secularized faith, the “Believe: sign over Ted Lasso’s locker room, or insist with the Mets “You Gotta Believe”, but deny ourselves Jewish faith? Why do we let ourselves be spiritual everywhere except here?

******************************

Our Torah gives us some helpful models.

Jacob. On the run from his brother Esau, Jacob lay down in the wilderness with nothing but a stone for a pillow. In his sleep, he dreamed of a ladder reaching to heaven, with angels ascending and descending upon it. God appeared to him with words of blessing and promise. When Jacob awoke, shaken, he declared: “Surely God was in this place, and I did not know it.” His story teaches that faith can come not in grand temples, but in lonely, ordinary places where we least expect it.

Aaron. After the unimaginable loss of his two sons, Nadav and Avihu, Aaron might well have turned away from God altogether. Instead, the Torah tells us that on Yom Kippur, Aaron dressed once more in his priestly garments and stepped into the Holy of Holies to perform the sacred service on behalf of the people. We do not know what was in his heart—perhaps silence, perhaps doubt, perhaps anger—but outwardly he continued to serve. His story shows us that sometimes faith is not certainty or joy, but simply the courage to stand and act k’ilu—as if we still believe.

Hannah. Despairing at not having children of her own but turning to God and praying for help, with bitachon— trust—that an answer would come in some way.

Job. When Job loses everything—his wealth, his health, his children—he sits in ashes, broken and despairing. His friends insist he must have sinned, but Job refuses to accept easy answers. Instead he cries out, raging at God, demanding justice, demanding to be heard. What is striking is not his patience, but his refusal to let the relationship die. Job’s story teaches that faith is not quiet resignation, but the audacity to keep speaking to God, even in anger and anguish.

Faith, in Torah, is not about never doubting. It is about daring to keep praying, keep acting, keep living as if. K’ilu, in Hebrew, “as if.” K’ilu is used in modern Hebrew the way we use “like” in English – like, it doesn’t really mean anything, but like, k’ilu, it does. Can we live as if God existed, k’ilu God hears our prayers. Because we don’t know—but we might choose to believe anyway.

So let’s try this together. A small experiment, because try as he might, Maimonides’ 13 Articles of Faith never took off, we never really wanted to agree to believe just one thing about God. We have so many choices in our choosing to believe. So here we go. Everyone:

a) Point one finger straight up. That’s the God who is above and beyond. Theologians call it supernaturalism, God up there outside of nature and us.

b) Now spread your arms wide. That’s the God who is everything. Pantheism, God might be everything, wherever you look, whatever you touch, it’s all God.

c) Next, cross your arms in an “X.” That’s no God at all.

d) Now: place one hand on your heart, and lift your other hand upward. Panentheism, this one is called. God is in everything, but also beyond everything. God is both with us and bigger than us.

e) And one last one: Swirl your hands – this is process theology – God in process, always changing and now hold hands with the person next to you – process theology holds that God and the world are in relationship, we influence each other, and as we change and grow, so God changes and grows. [release hands]

This is the wide range Judaism allows. No catechism, no one right answer. Just the courage to live as if.

Our ancestor Jacob said, “God was here, and I did not know it.” That could be our line too.

Agam’s whiteboard. The elevator ride. Jeff at the pool. Aaron in his grief. Job in his cries.

Yom Kippur asks us: Will we dare to live as if God is here?

Not because we solved the problem of evil.

Not because we figured out dinosaurs on the ark.

But because faith might just light us up inside, comfort us in sorrow, and strengthen us for tikkun olam.

So today, I don’t ask for belief. I ask you to consider the possibility of faith. To live, this year, as if.

Because maybe—just maybe—God was in this place all along. And we did not know it.

Your Story and Your Service: A Sermon for American Jewry (Rosh Hashanah 5786)

To watch the sermon, click here.

A few months ago I received something wonderful and awful in the mail. It was a postcard, it was green, and it informed me that I was being summoned for jury duty. Not just any jury duty, mind you, but grand jury, one full day a week for 17 weeks, every Thursday from August through Thanksgiving.

My first thought: A rabbi, serving jury duty in September? No way. Everyone I told agreed. I was sure I’d get out of it.

The appointed day arrived. I walked into the court building in Newark full of excuses. I had a letter describing my duties here. I wore my kippah – I don’t always wear my kippah in public spaces but I had it on that day, part of my strategy to get out of this – and a well-practiced script in my mind.

About one hundred of us sat in the appointed room. The clerk explained: one by one you will be called before the presiding judge. The judge will ask you one question: Can you serve? It is a yes or no question. There are two answers: yes, or no. That is all. Not your excuses, or your reasons or your backstory. Can you serve?

And then she said something that completely shifted the scene for me: “I know a lot of you came here today thinking you were going to get out of this. But this might transform your life. You might hear things that change you. You’ll get to know new people, and you’ll learn a whole lot about the community you live in. This country needs its citizens for the justice system to work. Can you serve? Yes or no.”

What a question for 2025. In Israel, the question of compulsory military service is heartwrenching, from the national conversation over the ultra-orthodox refusing to serve, to the families sending their sons, daughters, and husbands into a war zone. Here in America, we’ve become cynical, skeptical that our service – be it jury duty, voting, or participating in public life – even matters. “Can you serve” sounds less like an ethical summons than a request for a second helping of dessert.

Our ancestors asked this question, too. They knew the question runs deep. They gave us a phrase that is inscribed in so many sanctuaries around the world, including our own, right here above the ark behind me: da lifnei mi atah omed. Know before whom you stand. Our sense of service begins with that awareness.

Before whom do you stand today?

Last year on the shabbat of July 4th weekend, I shared a story that I love. It is the story of a man you’ve probably never heard of, named Jonas Philips, a Jew who came to America from Germany in 1756. He arrived in Charleston, an indentured servant to another Jew. By 1776 he had earned his freedom, and was living in New York with his wife and – get this – their 21 children. A patriot, Jonas Phillips joined the fight for American liberty and fought in the Revolutionary War. He loved the idea of this country. But he had a problem.

In Pennsylvania, where he moved after the British invaded New York and where he stayed after the war, you could not serve in the legislature unless you affirmed under oath that both the Old Testament and the New Testament were divinely inspired. Aware that no Jew could take such an oath, Philips wrote a letter to the Constitutional Convention. He reminded the delegates that Jews had “supported the cause, bravely fought and bled for Liberty” – but could not swear against their faith.

And at the top of the letter to the framers of the Constitution, he wrote the date: September 7, 1787, or 24th Ellul 5547.

24th Ellul 5547 – he put the Jewish date at the top of the letter! Recall there were no Jews participating in the Constitutional Convention, and George Washington and his peers must have been mystified by that opening line. Rabbi Meir Soloviechik calls these 8 words – “September 7, 1787 or 24th Ellul, 5547” – “the most audacious words in American Jewish history.” Audacious because Philips insisted he would not amputate his faith to serve his country. Audacious because he dared to hold both commitments together, his faith in America and his faith as a Jew. He stood before the founders of this nation, as a Jew, and he stood before God as an American. He knew before whom he stood.

So here we are, 238 years later, in a bewildering America. I wanted to share the story of Jonas Philips because I’m not sure we know what stories we are still telling about ourselves…or how those stories connect to our sense of service.

As Americans, we’ve become so focused on flaws—of our founders, our leaders, our neighbors—that we risk losing faith in the nation itself.

What story are we telling about America? Are we making it great, or greatly misguided? When someone is shot – on the street, at work, or on a stage – how is the story anything but one about murder, failed mental health care, easy access to guns and moral collapse? How can anyone justify the death of the innocent? When a news anchor is fired over remarks about the government – is the story about censorship, or accountability? What stories are we telling?

And as Jews, it is even worse. All year we’ve been hearing stories other people have been telling about us: that we (God forbid) are bloodthirsty, merciless, inhumane. That (has v’shalom) we care only about money or power, that we are among the cruelest peoples on earth committing the worst atrocities. This war is complicated and cruel, but we know for sure none of those stories is our story. None of those stories are true.

When a 12-year-old sat in my office recently and said about her Instagram or Tiktok feed: I just don’t know what stories are true or not – I thought: welcome to the club.

So here is my question for us, this Rosh Hashanah on the the eve of this county’s sesquicentennial: what stories are we telling about ourselves, and how do they enable us to serve?

Here is a story that can help us. The story of Joseph. Which is action packed, full of ups and downs. Some pretty terrible things happen to him, including his brothers planning to kill him, being sold off into servitude in another country, and Potiphar’s wife falsely accusing him which lands him in jail for many years. But he never loses his faith in God and eventually he becomes Pharaoh’s right hand man. You probably know the rest of the story: he creates a plan to store Egypt’s crops for the famine that he predicted in Pharoah’s dreams, and his brothers, who have run out of food, come to Egypt to beg for help, not realizing he is their brother. When he finally reveals his identity the brothers are astonished and terrified. They’re sure he will want vengeance. But that is not the path Joseph chooses. Instead he says:

“You meant it for harm, but God meant it for good.”

That line is everything. Because Joseph takes hold of the pen. He takes control of the narrative. Instead of revenge, he writes reconciliation. Instead of betrayal, he writes redemption. Instead of brothers fighting he writes a story of brothers helping one another and becoming close. Instead of letting others tell his story, Joseph tells it himself.

We choose how to tell the story. WE choose what story to tell. And that choice shapes not only us and our relationships, but the world.

This is what Professor Jennifer Mercieca at Texas A&M found, in a recent experiment with her students that I’m a little obsessed with.

Like many of us, Dr. Mercieca’s students were chronic doomscrollers, their phones “misery machines.” Instead of accepting it, she tried something new: what if they spent time hopescrolling? She had them create accounts devoted to solutions journalism—stories of problems solved and hopeful headlines. None went viral, but what happened to the students was remarkable.

Fixing the News, Sept 18, 2025:

“Many of [her] students reported that the experience was both illuminating and healing. “Before our Hopescroll project,” one wrote, “I really didn’t realize the amount of negative content I consume daily. I see scary news articles, I see people being mean to one another on social media, and I spend hours scrolling through posts that have no meaningful purpose.” Some students even noticed that their social media algorithms began to change, as they started to see more positive content on their feeds instead of so much doom.

What Dr. Mercieca’s experiment shows is that we’re not passive victims of algorithmic manipulation. We have more power than we think. Every time we share outrage bait or doom-laden headlines, we’re feeding a machine that makes everyone more miserable. But we also have the ability to choose differently. The algorithms will follow us wherever we lead them. We just have to decide what story to tell. This is not just true online. It is true in real life.

When that court clerk told me the story of jury duty, I changed. When Jonas Philips wrote the Hebrew date atop a letter, he changed the unfolding of history.

We stand (and sit and stand and sit) in synagogue on a weekday in September. The beginning of a new year, 5786. Both dates written in bold at the top of this page of our lives. We stand before our history, before one another, and – as our ancestors imaged on this Day of Judgment – before God who has each one of us stand one by one and asks us: Can you serve?

We know the answer is yes. But how do we go about it? First, by turning to these words over this ark as a reminder.

Know before whom you stand.

Today we stand before something larger than ourselves.

Know before whom you stand:

-God.

-History.

-Future.

-One another.

We stand before our grandparents who sat in these pews, and the ones who perished so that we could.

We stand before our grandchildren who will inherit this earth, and the wars we do not turn into peace, and the messes we do not clean up.

We standing before one another. We stand before history. We stand before the future. We stand before all we hold dear. Da lifnei mi atah omed. Know before whom you stand.

And then, decide: what stories will you tell this year, and how will they enable you to serve?

The blessing we offer one another at this time of year is Ketivah Tovah. May you be inscribed in the book of life.

But I think this year we need to think of it this way: May we inscribe the Book of Life. May we fill our next pages with stories of sweetness, of progress, of hope, of all the ways we serve.

May we stand before one another this year and write one another into our story in love and in peace, and most of all, in service. And then may God seal it for good, gmar chatima tovah.

Let us say: amen.

Grandparents

You might expect this week’s blog to be about Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur or even about Hispanic and Latino Jews since September is Hispanic Heritage Month, but it’s about grandparents.

Why? As we approach the High Holy Days, many of us spend time with families and think about our relationships with our grandparents. Those of us who are older may even say kaddish for them during the Yom Kippur Yizkor service. Children hopefully look forward to spending time with their grandparents and forming memories. No matter what, none of us would be here without those grandparents.

And by the way, the Hallmark Holiday Grandparents Day is celebrated on the first Sunday in September.

Here’s a selection of books for kids and adults celebrating grandparents:

Berest, Anne. The Postcard, which suddenly turns up, is at the center of this fictionalized history-mystery about the author’s great-grandparents who were killed in the Holocaust. (FIC)

Kalb, Bess. Nobody Will Tell You This but Me is a memoir of Kalb’s relationship with her now deceased grandmother, from whom she learned about life and love. (BIO)

Shalev, Meir. My Russian Grandmother and her American Vacuum Cleaner is the author’s story of his Russian Jewish family told humorously and lovingly through his super-cleaner grandmother. (BIO)

Tuininga, Josh. We Are Not Strangers is a historical fiction graphic novel set in Seattle during World War II. Marco’s father was a first-generation immigrant who befriended and supported the Japanese-American community after Executive Order 9066, which sent Japanese-Americans to internment camps, went into effect. (FIC)

Davis, Aubrey. Bagels from Benny is a retelling of the tale of bread left in the ark for God to eat. Young Benny helps his grandfather in his bakery and learns some important life lessons. (E)

Heller, Linda. The Castle on Hester Street, where Julie’s grandparents lived — was it a castle or a dump? It all depends on your point of view. (E)

Oberman, Sheldon. The Always Prayer Shawl has been handed down from one generation to the next. Beautifully illustrated. (E)

Rosenberg, Madelyn. This is Just a Test takes place in 1983 during the Cold War. David Da-Wei Horowitz is worrying about so many things: his upcoming bar mitzvah, his grandmothers (one Chinese and one Jewish) who argue all the time, a trivia contest, and his best friends who don’t like each other. (JFIC)

Saltzberg, Barney. Tea with Zayde (Grandpa) is a delightful story of teatime with Grandpa. Perfect for little readers, it has a surprise ending. (E)

Schwartz, Howard. Gathering Sparks introduces the concept of tikkun olam. (J398.2)

Desire Lines

My walk to Oheb takes me across Grove Park. Dotted with giant, 200-year-old trees when we moved to town a few years ago, the ash blight has turned the park into a sunny field distinguished by just a solo playground. The paved walkway encircling the park serves as a track for the morning runners and stroller-walker set, and keeps us off the beautifully maintained green grass that no longer encircles age-old trees.

My walk doesn’t really start where the paved pathway does, and so I cut across the grass. I’m not the only one. There is a dirt groove, a ribbon of brown icing across the green frosted cake of lawn. Many of us, it seems, needed – wanted – a path where there wasn’t one, and so ended up (without organizing, without trying to) creating one of our own.

This is known, in urban planning parlance, as a “desire line.” I love that. I love that there was a plan, and it was a very good one, and still serves so well: the park, the grass, the playground. But over time, desire shifts. Needs change. “We paved the paths already!” you can hear the frustrated urban planners sighing. “We planted the trees and set it all up!” Yes. And also, there’s this desire line, over here. Come look at what else.

We have wrinkle lines, frown lines, tanning lines, to say nothing of the scars, tattoos, and other evidence of desire—or its opposite—written in these bodies of life lived. Desire lines are the paths worn into the ground by repetition. Unplanned but chosen, over and over again.

I love that the launch of the school year coincides in the northern hemisphere with Rosh Hashanah and our High Holy Day season. Right now, it is Elul, the last month of the year 5785. Our kids have a new start with new teachers, and we too crave a new beginning and give it to ourselves thanks to the Jewish calendar. A new year, we declare. The shofar calling us, beckoning us to see the desire lines we’ve unwittingly sown into the soil of the four seasons behind us. Looking back is the only way to see the path we are on.

“Please teach me Your way,

And lead me on a level path…”

(Psalm 27:11)

How do we stay on level ground? How do we make sure it’s not all uphill—or even worse, all downhill? Psalm 27, the psalm of this season, can be on our lips every day from now through Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, straight on through the end of Sukkot. Are we asking for God’s help, or for one another’s? Both?

What kind of friend do you want to be? What kind of partner, what kind of child to your parents—be they dead or alive? What kind of parent to your children—be they dead or alive? Whom do you desire to become in 5786, and what paths must you tread to become that person?

In the coming weeks, we will, I hope, have much time together. It feels like a new beginning we make together. With all that we desire. My path brings me straight across Grove Park to each of you. I hope to sing with you, and pray, and laugh. I hope to share tears of joy and sorrow, and stories of love, hope, and faith.

May the desire lines we tread together lead us to the places we dream of going. May they guide us into hope when hope seems far, into strength when the way feels steep, into joy when the grass grows over old roads and we find ourselves ready to walk anew.

This year, may we walk not alone, but together. May our steps make new grooves in the earth, worn not by habit but by heart. And may those paths, unplanned but chosen again and again, carry us—toward one another, toward the Source of Life, toward the future we dare to desire.